Madraspatnam

In the late years of his life, Jasper Holmes asked me if for the purpose of this short story he could dictate his memories of an extraordinary three years he spent in India as a young child, including his mother Miggie’s mysterious episode with the paranormal. Every word of this tale is true and came from the specific recollections of Mr. Holmes, with photographs by his late father Hubert. After a handful of interviews, I was able to reconstruct his recollections into a narrative, something like the old walls of his loft in Manhattan’s Soho, patched and re-stuccoed over the course of a long period of time, but still very much true to its original essence.

****

Terminus

In nineteen fifty-nine the U.S.S. President Monroe, a merchant ship requisitioned as a troop ship in the second world war, having returned to merchant service, sailed out of Cochin in the lengthening shadows of dusk. Among its few passengers were the Holmes Family of New Delhi at the end of their final year of civil service in India. With the drama of a B movie, the little freighter voyaged west across the Indian Ocean, up the Suez Canal and across the Mediterranean, passing Gibraltar and sailing north. Schools of Bottlenose Dolphin swam with the ship in expansive numbers as the small ship traversed the Indian Ocean, its clean waters packed with food.

In his mind Jasper Holmes harbored a faint memory of their voyage homeward, partially gleaned from photographs and a handful of sixteen millimeter movies his father had struggled to create. Those were the days when, with study, one controled the camera manually. His father was always frustrated, but somehow a few managed to survive the decades thanks to the boy’s interest, becoming a foundation for his reminiscences and helping to clarify and complete the visualizations in his mind.

The children stood at the gray pipe railing under the watchful eye of their mother Miggie. Rust peeked through gray flakes of frayed enamel. It was no more than a bucket after having fought the Japanese barely a decade previous. Their passage aboard the rusted hulk was the typically creative mindset of their mother and her taste for adventure. As the docks and jetties passed, almost clairvoyantly, the family mourned their last contact with a world of stark contrasts, one they’d had the astonishing good fortune to have been a tiny part and one they’d devoured completely without wasting a single moment.

Standing on deck with her arm shading the late sun, the bucket inched itself away from the busy pier and into the canal to face the sting of the ocean’s breath. Her movie star looks, disguised in a plain yellow shirt and khaki shorts, gazed lovingly at her children in a rapturous, teeth-and-gum smile decorated in signature red. That was all the embellishment she allowed herself that day. Her impossibly radiant face—the epitome of kindness—facing the wind and kissed by the ozone. The gentle spin of slow propellers on the outgoing flow took them gradually out into the stark juxtaposition of the open ocean and away from the magic of India.

In the lee, their father, a tall collegiate man with matching good looks, was behind his camera. Rarely present emotionally, he couldn’t help an aloof nature, choosing to be little more than an animate shadow.

After the long voyage they docked at South Hampton and traveled west to London, a city that still bore the scars of the Blitz. His father had been a navigator on a B-26 bomber that accompanied Roosevelt to Yalta; his mother a dedicated volunteer with the Women’s Army Corp. At age seven Jasper Holmes fully understood his parents had been part of a great Allied force that had fought and won a bitter conflict at great cost in lives and property.

Like missing teeth, empty lots stood where buildings had met the savage anger of Nazi munitions. With only party walls left, the colors of cheerfully painted rooms and the vague outlines of the stairwells that once connected them, was all that flanked the dead spaces where people had lived and perished. For his little mind, it was incomprehensible to believe what others had done to our closest friends.

They were a small family of four individuals with rich imaginations and a natural love of history. Touring Europe that final summer they’d almost bought a castle in the Dordogne Valley of France, agreeing between them they’d call it, Our Castle. The world was finally at peace, but with much of its antiquity in ruins before their eyes to make sense of.

****

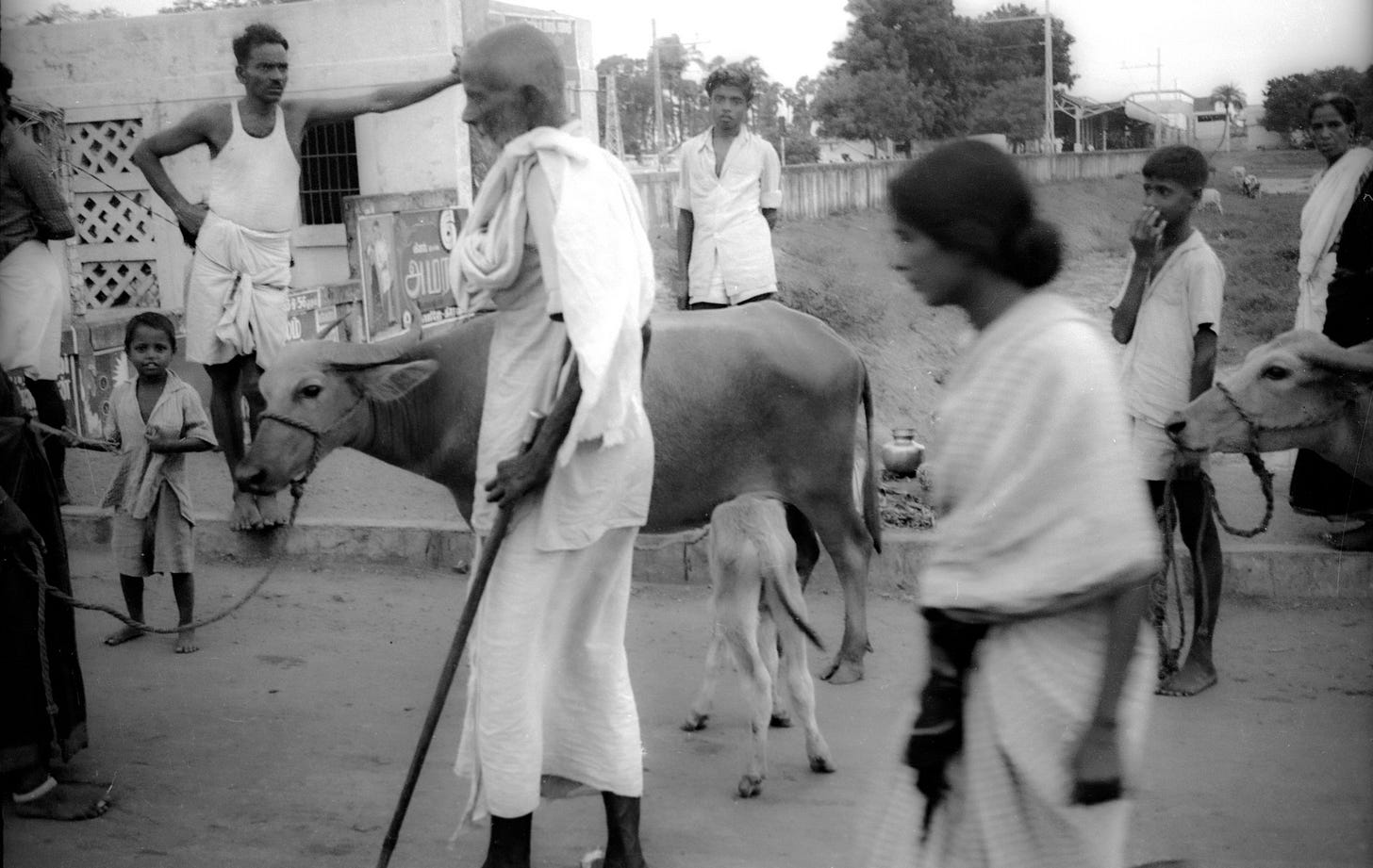

Three years in India had been a front row seat on the consolidation and modernization of ancient realms built from the scraps of crumbling temples and vanishing jungles, its people still helpless on the razor’s edge of survival. As people will they yearn for more, unaware of what they have, or don’t have, until, to the great disadvantage of history, it’s gone and forgotten. For better or worse, change came in the internment of the past, in waves of entropy along the march of progress, devalued in the chaos of the present-day.

In their young lives, their father’s shining hour had been bringing his family in and out of an exotic dream, a rhapsody they would carry in their hearts for life. He had done the right thing bringing them to Asia and into the enlightenment of a complete unknown, something rare which seemed to squirm and slip from one’s hold, finite and temporary, but something that would live on in their minds, like dead relatives and lost friends.

The boy’s evocations would soon enough be of a century past, stained into the walls of the great house in Madras—his father, the precarious dignitary—his small family in tow, running an English library amidst beggars and holy men in saffron and pink, random devotees of ancient beliefs and customs in a feedlot of oppressive hunger.

None of them knew exactly what Hubert Holmes really did, a melancholy man with a secretive nature that tightly kept its thoughts secluded and hidden from sight.

The palatial home surrounded by rain forest had been the boy’s reverie, his secret place of unsolvable conundrums, to be pondered and filed away in the vault of his mind for future dissection. Like prayer boats on the Ganges decorated in white light under veneers of stars—his reverie was a gorgeous set in the opening act of a play—his to share and draw inspiration from in the extended reverie of his future. He’d consumed impressions of it like investors collect great paintings, racked in the expanses of his mind—and souvenirs of reminiscences frozen in boxes of images, and letters, and fragments of thoughts and words, stitched together into what would become a frayed but complete tapestry of a dream that had once come true.

****

Genesis

They’d traveled to India that first year on Pan American Airways in the earliest era of transatlantic flight. The adjustable air vents and overhead lights swiveled and lit with the push of a finger, mesmerizing the children in their buckled seats. It was Jasper’s invitation to imagine himself in headphones and gold leafed cap, in a dark suit with lappels. He captained his obedient airship through the panorama of his imagination, a blue horseshoe spread out before him in a silver bird catapulting through the curvature of darkening hemispheres.

They slept in foldout berths above their seats. As dusk descended and evaporated from the heavens over unknown lands and vast oceans lit in pastel, glamorous stewardesses in blue-gray, military-styled uniforms with gold wings pinned to their breasts, prepared the cozy births after martinis and hot meals. In awe, their mother, the artist, would be glued to the window above the gravitational abyss of blue and green sprinkled with clusters of flickering city lights.

The airplane lashed and battered, buffeted by the jet stream fighting its way in and out of a broken ceiling of cumuli, like bleached coral heads in a dead sea. As they lay in their berths searching for sleep, they pondered the unimaginable, relieved to finally be close to India—the prodigal family eager for unknown tastes and spells and their tiny slice of an exotic place unknown to Americans.

With the nineteen-fifty Constitution of India, a new state had been founded, Madras, and the city on the Bay of Bengal of the same name. Madras began as a hypocorism for Madraspatnam, a fishing village where the East India Trading Company had built a fort and a trading post in 1639.

They would soon be part of a colony of Americans eight thousand miles from home. Madras was not a place for weak-tempered individuals. Some seemed despairing of the isolation and not capable of appreciating its wonder. If you could handle it, and possessed a rich enough imagination, it forced you to see that East Indian reality was built in complex layers of transcendental experience. Anything was possible in so magical a milieu.

“This isn’t Kansas anymore,” they liked to say, holding their gin and tonics, moaning endlessly about missing the States. But all agreed, compared to India, home was staid and less fascinating, and living in a foreign country seemed to bring with it a healing lift.

****

Jasper remembered little of their first trip by land to their new home in Madras, or where they’d even landed all those years ago.

He was four years of age at the time, the elder of two siblings, his sister Allyson just two. As adults their experiences would be preserved in hazy anecdotes, wrinkled snapshots, faded Kodachrome slides, and 16mm Bell & Howell movies—like stone tools—collected, logged and defining. They would hallow them like pieces in museums full of cobwebs—relics in fragile collections—well-loved if barely resistant to the ravishment of time.

The family moved into an enormous, two story home with a columned patio of heavy, white plastered walls and a red tiled roof. Their furniture arrived from the States in huge wooden boxes. The nation-building government of the United States assured the house’s inviolability, stable on a surrounding sea of privation.

Reserved for U.S. State Department officials, the house sat confidently like a royal portrait, a magic embassy in a sparse jungle of palm and banyan and faithfully groomed lawns with walkways lined with roses and tropical shrubbery. Coconut trees clustered together in the jungle setting where elephants and tigers once roamed, and troops of primates had fattened themselves on wild fruit, gazing down safely from treetops, grooming their young.

Not yet completely extirpated by the ruinations of men, a kaleidoscope of tropical life trembled on—parallel lives in a partially intact system on the inviting stage of the equator’s pulpit, an embodiment of Rousseau’s vision of a composed and gentle wilderness.

Mango trees offered their gifts, and towering banyans sat like saints among the paths, growing slowly to immense sizes with arms like living stalactites, growing down and deep into the rich hummus of the earth.

****

END OF CHAPTER ONE

TO TOGGLE BETWEEN CHAPTERS USE NAVIGATION BUTTONS BELOW

****

Tony Heath is an artist, jazz musician, activist and writer of fiction and essays in Arizona. He and his wife, Kate Scott, co-founded a wildlife advocacy on their ranch in Cochise and Santa Cruz Counties.

Photographs © Tony Heath