Exotica

As night approached, a fearsome racket of living sound rose from the jungle. The helter-skelter flight of winged mammals cut through the fading light and softening heat of the sweltering day. Massaging the imagination were the cries of small animals rarely seen, and the lisps, chirps and trills of millions of insects. Carnivorous birds hiding in the thick canopy waited patiently for darkness, eager for the murky pitch of night and the emergence of prey.

And there was the curious tapping that echoed through the vast spaces, moving about without identity through the brightest and blackest nights, inhabiting their dreams as they slept without awareness.

The Holmes luxuriated in the exotica of the night. Their civilized life in the United States of nineteen hundred fifty-six, to which they would return, was all but forgotten in this distant paradise, a pair of shoes so large it might take centuries to grow into, or so it felt.

****

With all the education, wealth and advantages of Brahmins, as foreigners the white family were technically Untouchables in an entrenched social system so varied and complex the boy, a bright and imaginative child, was too young to make any sense of it. A mannerly child of tireless curiosity and unimpeachable respect, Jasper, a perfect American, treated all the members of their tiny hamlet as equals and with goodwill.

Still primitive and steeped in traditional culture, only recently had India become a Republic, a conglomeration of states surrounded by ocean on three sides and the Himalayas to the north, but still a place of implacable destitution. Piety and devotion to gods and higher powers was the people’s nostrum. Encumbered by deprivation and a caste system separating everyone from each other based on uniformly unattainable wealth and education, the people were invariably ruled by a select minority with all the advantages, a back that couldn’t be broken.

The home included a competent, hardworking, and well-meaning staff of Vaisyas, Sudra, and Untouchables living nearby. Back home, servants had been unknown to the young Holmes family, but here it was an appreciated perk in an unknown and challenging land faraway from Massachusetts.

Jasper remembered six dear souls whom in time they would grow to love like family, dependable and good-natured, and dedicated to their work.

The help lived in crude huts made from sticks and dung, small detached quarters in the shadow of the majestic house. For the day’s work a short distance away, the servants rose to the tender flush of first light and the rooster’s crow. In the fading stillness of morning, nightfall in retreat, the shacks exhaled twists of gray rising mercurially into the warming air like curvaceous dancers in bangles and beads, before disappearing into a high awning of coconut palms.

Before the sun reheated the day, they walked to the big house along narrow dirt paths teeming with unseen mammals and unimaginable insects that might pester or sting; or carapaced beetles crossing their path on deliberate business; or dangerous snakes in frightening colors decorated for self-defense.

In the high trees sat birds with odd shaped beaks, beautifully feathered by the grace of the dieties. In the cool morning haze, the birds moved about hunting for their first meal, a beetle on his way or an unlucky moth, calling others to follow in the rising sun. With unsurpassed elegance, painted butterflies came out of their seclusion hidden from the night, exploring the lush plantings of the gardens, searching for sweet nectar in beads of falling dew.

One day Jasper felt a fearsome sting. His hand had reached up under a swing made of wood and rope hanging from a large banyan tree next to the house. A nest of hornets unleashed a painful warning, a universal lesson he would take with him through life. Never again did he fear bees, understanding that life required them to protect themselves, and he to be vigilant. Bees had no quarrel with anyone or thing until it came to their self-defense, which they were loathe to engage in without clear cause.

****

Of the six servants, Jaipaul and his wife, Katherine, played the most critical part. He was a butler of sorts, and she the aia. She watched the children to the relief of Miggie, an enlightened and loving mother who also wrote poetry, painted, and read difficult books, putting Hubert’s frequent absences to good use. An autodidact, she believed the meaning of life lay in the power of self-knowledge, and that spiritual growth ended only at death and that no human had proved what came after life. In practice, she believed that life was a preparation for a total unknown that lay beyond, the purview of quantum theory, or ideally, a loving Great Spirit.

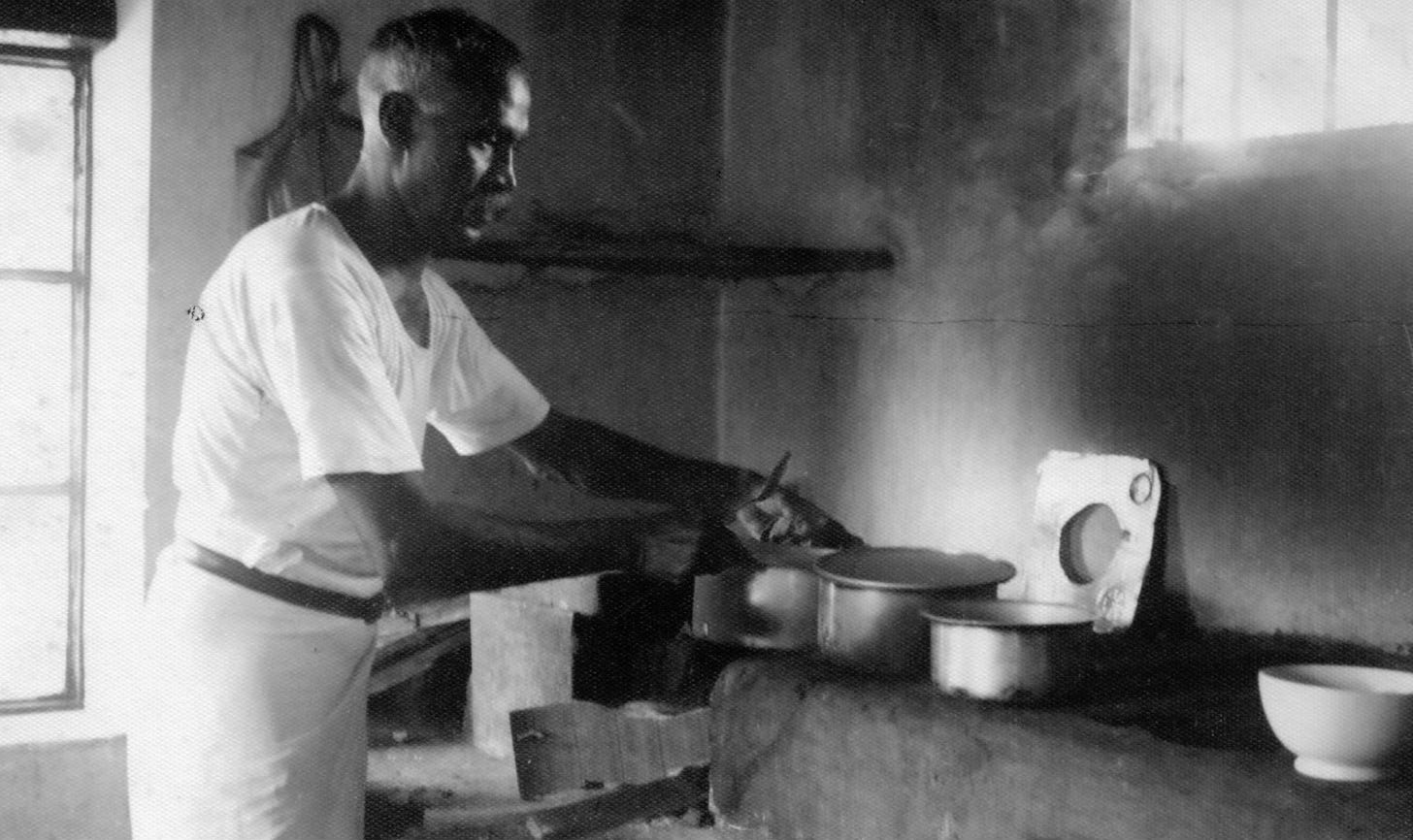

Next was Ragu the cook. He dressed shirtless in white cloth and sandals that kept him cool tending to his blazing ovens. A stern man with a gray mustache and a crude turban, he was devoutly Hindi, as were the majority of the people of the State of Madras.

Nobody but Jasper questioned the irrefutable fact that the home’s kitchen was Ragu’s private domain—and should be—a place guarded closely for the sanctity of their food.

His stove was made of hardened dung that somehow withstood the heat. In the morning he carried the wood and kindling he needed for the day’s meals to the semi-open kitchen behind the dining room. One afternoon, Jasper was poking around the kitchen when Ragu’s malcontent exploded like a stick of dynamite. Holding two flaming sticks belching smoke, he chased the boy into the main house screaming in Tamil like a bloodthirsty warrior, no doubt to make perfectly clear the boy was never again to be allowed in his kitchen.

A four year old learns quickly and is forgiving. It wasn’t long before Ragu grew friendlier to Mr. Lucky Man, as the servant’s nicknamed him after so many close calls. The rules had been etched in solid stone and there would be no further violations from the little wise guy.

At mealtimes, Jaipaul and Katherine doubled as servers traveling back and forth up a long series of steps to the dining room where the family sat at a large teak table. Their mother’s choice was always Indian food, curries with poppadoms and a variety of sweet and sour chutneys and assortments of fritters on simple platters with seasoned sauces.

****

One evening the family was sitting at dinner. Jasper was the first to notice it through the large picture window overlooking the lawn. In sight of the whole family, an impressive reptile emerged confidently from the underbrush. A King Cobra raised its oval head glancing up at them through the glass. It had curious eyes on the front and back of his head, the latter faux, designed by nature to confuse and bewilder its enemies. On the front of his head he sported a garish mouth with what looked like the smile of a psychopath, perfectly designed to frighten without mercy, but thankfully without follow through. He panned the path ahead as he moved on through the grass assertively, his upper body fully erect and strikingly at attention.

It was close to the planter his mother had frequented that very afternoon, running her hands through the dark soil, on guard for the unknown. The unknown had arrived that evening with dinner: twelve feet of undulating tissue, slowly making its way across their view, its business very much at hand.

Nothing could be done about snakes. The Holmes were watchful but not afraid, as venomous creatures were everywhere and as naturalists they were supportive of diversity at whatever the risks. Life in India required that one honor and respect all living things in a country on the equator teeming with life. Man’s fear often got him into trouble unnecessarily, ending in deadly standoffs for the other’s territory.

The full staff included two gardeners and a nightwatchman. For the compound’s defense and to exact punitive action when required, the watchman bravely carried an enormous stick and a machete at his side. Like Ragu and the gardeners, he was dressed only in sandals and loose cotton fabric around his loin allowing his legs to show. Weather permitting, they were often shirtless. The watchman served as the local gendarme standing at the front gate all night long guarding for thieves and kidnappers prowling under cover of nightfall with sacks on their backs for holding and carrying off children.

To Miggie’s chagrin, the well-being of nocturnal life making its way through the jungle was often in jeopardy, threatened by irrational instincts ingrained in the watchmen by fear and past experience, which one could hardly entirely blame them for. Still the watchmen often killed venomous and harmless snakes for sport in a knee-jerk reaction much to Miggie’s dismay.

Lastly, two groundskeepers applied their magic and hard work to the elaborate and beautifully manicured gardens that wrapped the site in an opulent tropical pageantry.

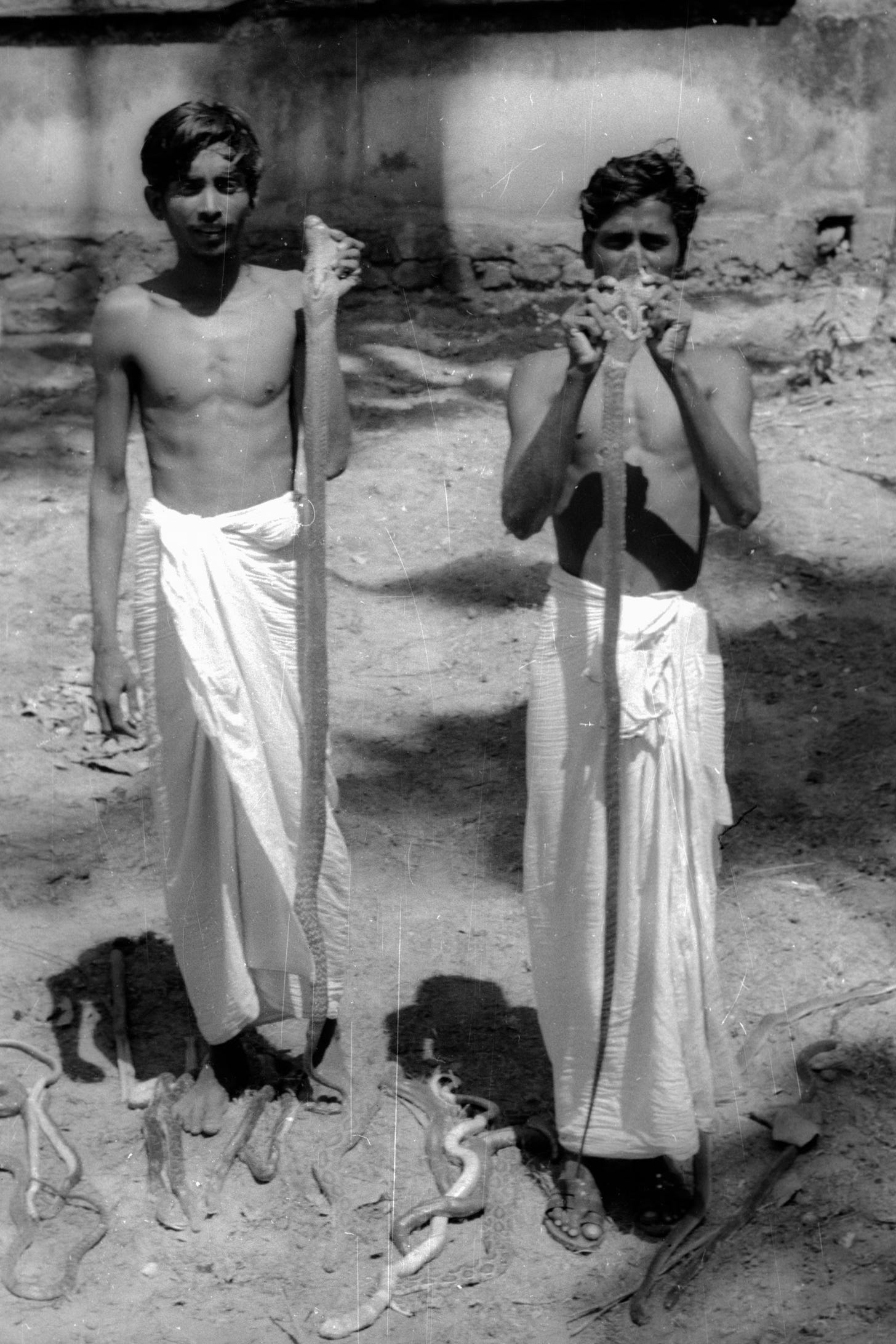

It was not unknown for the gardeners themselves to stumble on a cobra, its unspeakable grin beaming at them, hissing and spitting, as it rightfully glided its way through the underbrush. But that was hardly how the natives saw it. In the wild the cobra’s worst enemy was the mongoose. Domestically, their worst adversary was a savvy gardner with a machete as sharp as a razor, or charmers with pungi and wicker baskets to hold them prisoner as showpieces, hypnotized by their flutes.

A fearsome lover of nature, if granted, a trifle naive, Miggie pleaded with them not to kill snakes despite the risks, especially the harmless snakes that seemed to be everywhere, the ones she tirelessly tried to identify in her manuals. In truth, she had little control over the native workers fears and instincts to kill gleaned over thousands of years of self-defense. Her sentiments demonstrated Miggie Holme’s great respect for natural life and the outdoors. But she was helpless against man’s instinct for self-preservation.

The children were taught to be very careful. Snake bite was a common and often fatal accident in India, and almost always the result of mistaken identity, as snakes are not aggressive unless threatened by the irrational fears of mankind.

*****

END OF CHAPTER TWO

TO TOGGLE BETWEEN CHAPTERS USE NAVIGATION BUTTONS BELOW

****

Tony Heath is an artist, jazz musician, activist and writer of fiction and essays in Arizona. He and his wife, Kate Scott, co-founded a wildlife advocacy on their ranch in Cochise and Santa Cruz Counties.

Photographs © Tony Heath