Chapter Three – A Family

Hubert Holmes ran an English-speaking library in Madras when he wasn’t off on business trips through the hinterlands of the undeveloped Republic. He was a Harvard educated mid-level statesman, but nobody really knew what he did. Later on after returning to school in the States, Jasper’s friends insisted his father was a spy. Jasper had even found a tiny camera abandoned in a box of his things in their storeroom in Connecticut. To his friends it was proof his father was James Bond in the flesh. Jasper knew otherwise—that his father was quite incapable of anything surreptitious—just a scholar who kept to himself most of the time studying Russian.

In Madras he went off to work each morning leaving his family in the capable hands of Jaipaul and Katherine and the groundsmen. The nightwatchman slept all day. Ragu would be busy collecting firewood and stoking his oven for the day’s formal meals, or prepping for a cornucopia of Indian delicacies, his cooking one of the best things about life in the lordly official residence.

****

Miggie Holmes had grown up on her parent’s farm in Virginia. When she was the first of four to die at seventy-two, her brothers and sister, a quarrelsome bunch that never agreed on much, conceded that she, in every way shape and form, was the pick of the litter. She was as bright as a full moon, emotionally intelligent, lovely to look at, and the most generous and caring individual Jasper ever recalled knowing in his later years. He calculated, to the very day, when he’d exceeded her life span. All he could think of that day was what he’d done to deserve the gift of a longer life. Was it simply the sledge hammer blow of chance, or, as he believed all those years past when she left them that day, a bitter cruel joke.

Long after their life in Madras had passed and gone, the parent’s marriage ended in divorce after seventeen painful years of incongruence. As Hubert was a private and quiet man and hardly forthcoming, the loss was a staggering blow. Had Miggy been too assertive, or was it that she was so perfect she’d threatened his self-esteem? Their father told them little about India, so when ovarian cancer took her life at seventy-two, she took a treasure box of recollections with her to the hereafter.

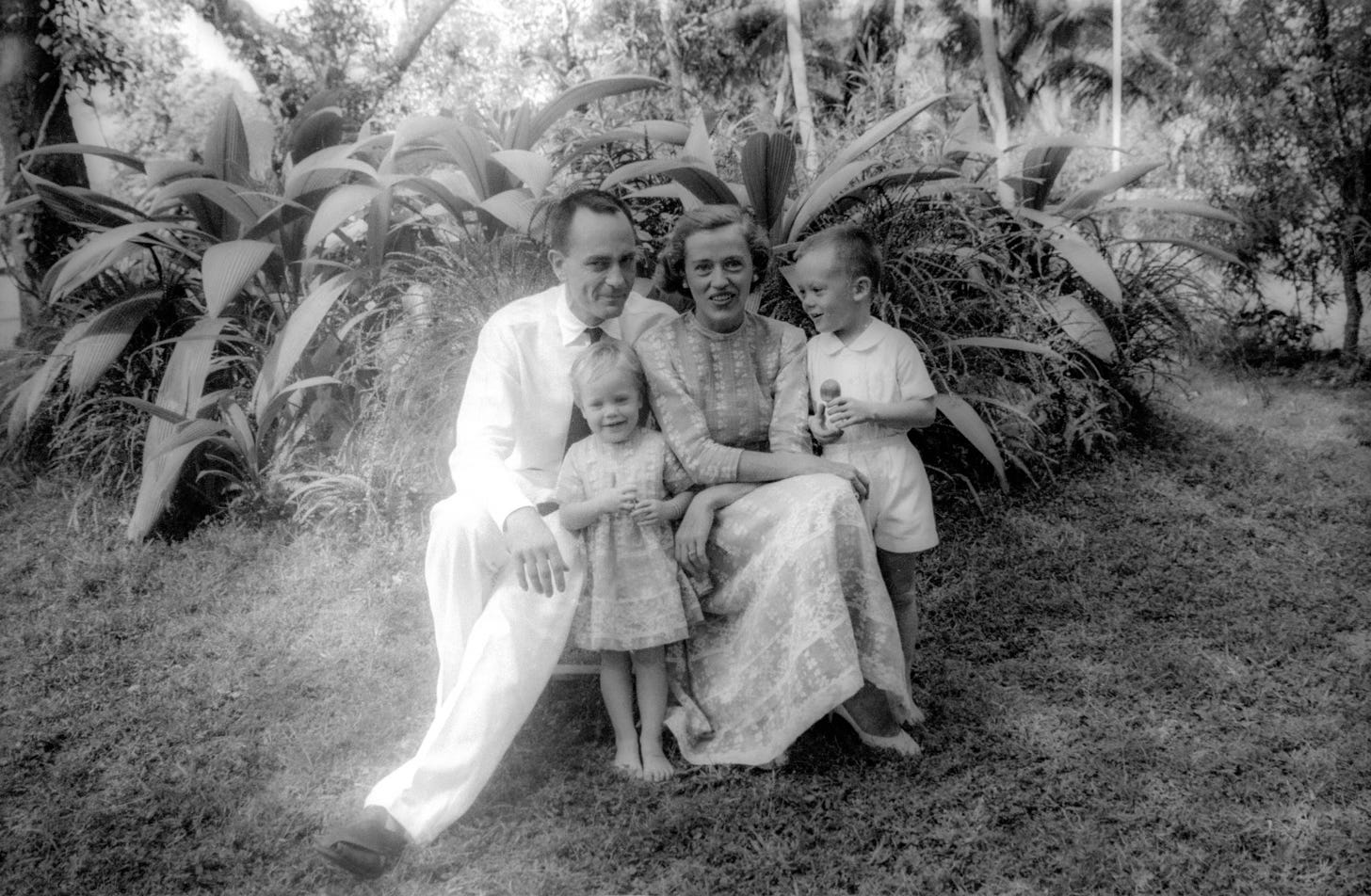

Jasper would be forced to rely on his own memories and the few she’d left him, and a small number of his father’s photographs and movies preserved in Jasper’s files for what eventual fate was anybody’s guess.

****

For months after they arrived in Madras the children were oblivious to the warbling of their wild surroundings. They ached for home and especially their grandmother. Under the watchful eye of their aya, in time an insatiable desire to see and explore the compound’s mysteries became their routine. They underpainted the blank canvasses of their minds with reticent impressions of what was essentially three rings of enchantment around every corner.

Jasper was constantly active with a penchant for trouble. He appeared to have already developed a highly inquisitive and curious mind, but cloaked it in sensitivity and insecurity inherited from his parents. There were dichotomies in their lives—a tolerance for risk, versus a keen sense of self-preservation; and a desire for personal growth, versus a lack of drive to compete and win.

He exasperated everyone with a single word, “why?” It was as English word the servants quickly learned and ignored, muttering querulous frustrations in Tamil, exasperations their white employers couldn’t possibly understand.

Allyson, still in diapers, had a clinging side and stayed close to her mother. Her penchant was to scold the help in baby language, staying close to home and pointing her finger incessantly. She rarely got into trouble except when she threw something at her brother, who from his mother, had already picked up a fondness for teasing, an endless source of aggravation to his more demure baby sister.

Hidden in the shadows of the mysterious setting were risks unknown and unlike anything in the hills and dales of New England. A step away could be fatal, so the servants made a lot of effort to keenly watch the children at play and educate the parents as well.

One day, an escaped herd of water buffalo came charging brutishly past the house, herdsmen in hot pursuit. Within seconds Mr. Lucky Man was on his feet running in their direction yelling assertively, “Get those dam-it buffalo out of here!” Despite his sensitivity, he could be a bossy four-year old if necessary and understood he was the little man of the house when his father was gone, which required him to take responsibility and keep watch over his mother and little sister.

They were actors in an exotic film in bright technicolor, a projection of magic and intrigue unlike anything at home; a nail-biting drama on an ethereal location surrounded by the chaos of millions of mysterious lives in all directions. This was not a movie sanitized for children sated on popcorn and candy, parked in front of big screens in safe drive-ins in the blandest of suburbs.

Life in Madras flowed like gentle but deadly lava—the ancient and the unknown—a living divinity far from home, guarded by oceans too vast to imagine.

****

As if being in India was not difficult enough, Jasper had a natural inclination for trouble. You might say he was prone to accidental self-harm. Little or nothing could be closer to the truth. Calamities seemed to befall the little lad with troubling regularity. Doting servants kept a close watch on the one they called Mr. Lucky Man.

The first such incident was a speck of material that lodged in his left eye. They were forced to race him to the offices of a Dr. Watson, a female surgeon of British ancestry who petrified the little boy, even more than the cobras, and it wouldn’t be the last time he saw her.

Years later he still recalled the smell of the ether and violently tearing with all his might at the white gauze covering his mouth and nose; as if his fate had been determined that day and the Reaper himself stood at his side next to the operating table, his life over at so young an age. His mother would be devastated. He quickly lost consciousness and awoke in what seemed a flash.

His mother, sister, and he would often travel about the small city doing errands in their convertible Studebaker. The boy, naturally reckless and a born risk-taker, would stand up in the front seat leaning against the windshield with both hands raised. He would jubilantly wave his arms and point his index fingers into the wind, like a teenager at a rock concert.

One day he forgot to close the door all the way and his mother hadn’t double-checked it. She too could be reckless and even comedic about it at times. He recalled the three of them in Antibes. His mother had drank an entire half bottle of red wine and was feeling fresh. She drove down the quay pretending to be drunk, weaving pretentiously for the amusement of the children and waving to sailors that wanted a piece of her.

But this was Madras, a filthy third world setting. Around a steep corner the door had flown open and Mr. Lucky Man was gone in a flash. Catching air briefly, he rolled along the street before his mother could even react and stop the car, it all happened so fast. Again, all these years later he could still recall the sensation of rolling and the blurred circling background before he came to a halt. With no broken bones, he was not badly injured except for scatches over three quarters of his body. It was India and with no broken bones his injuries were still a serious matter.

Miggie rushed him back to Dr. Watson’s institutionally-green painted office. He was placed on a gurney and rolled into the very room he’d recently had his eye operation. It was a scary place with odd smells, syringes with long needles, tools for probing, scalpels, and glass jars full of cotton.

With horror, he recalled the brushing of the shallow wounds with disinfectant and no anesthetic. Buckets of tears ensued. Each scratch, many the size of a half dollar, had to be scraped by Dr. Watson’s own hand with cotton swabs soaked in medicine, lest he succumb to any number of germs crawling opportunistically on the soiled pavement of the Indian street he’d rolled down.

That was the last of his early calamities, until their last year in New Delhi when he dropped a fifty pound piece of cement on his left middle finger. Not daring to tell his parents, he allowed it to become infected with blood poisoning all the way to the bottom of the finger where it meets his wrist. Little would be left of the tip of his finger after months in bandages and shedding layers of skin. For the rest of his life, in public, he would bend the finger from sight, lest somebody notice its deformation.

****

Miggie’s mother was barely five feet tall. Everything about her was old-fashioned. The memory of his grandmother in India holding her green umbrella for protection from a blistering sun was not born of a Kodachrome slide, but etched into Jasper’s memory from life itself, clear as crystal stone, detailed and intact at seventy-three.

For an extended stay, she’d traveled to Madras eight-thousand difficult miles. The children had been jubilant with anticipation. Other than their mother, they held no other person in higher esteem than Delores Kendrick Neary. She still lived on Cedargraves, the farm Miggie had been raised. With her husband Clayton and their two sons, they raised the finest black Angus beef in Orange County. Their home was an enormous Greek Revival mansion built on a hill above a glistening lake. At the bottom of a deep valley, the lake was surrounded by the steep foothills of the Blue Ridge. An enormous flock of Canadian geese graced the green lake, a site of shimmering perfection. In the distance, a row of iridescent mountains completed a scene of stark tranquility like a Hudson River School masterpiece.

In young lives lived place to place, in their blossoming minds the farm would always be their special place, and their grandmother its leitmotif: an anachronism in antiquated clothes, snow white hair, and her small green umbrella.

Her visit to Madras had coincided with the arrival of the snake charmers. They would collect what turned out to be eighteen deadly poisonous snakes and countless harmless ones. They deposited them in crude, finely-woven burlap bags before being killed and burned in a large fire, all to Miggie’s horror, dismayed by the injustice. Against her better judgement, based on her absolute love for all life, finally, in light of the ever-present danger of snake bite, she’d reluctantly agreed to hire the snake handlers for just pennies. But she insisted on giving them much more. The snake’s lives had to be sacrificed, a moral quandary she couldn’t remedy being the lover of life and all living things she was.

During the hunt, the wise old lady with her two grandchildren glued to her, traversed the grounds bravely cautiously watching the charmers from a distance collecting the doomed serpents, animals that were actually harmless if not disturbed by thoughtless fearful people.

On one side of the house was a series of deep square pits of unknown origin connected at the surface by dirt paths. If not very careful, a person could slip and fall a distance of twenty or more feet to the bottom. Wrapped traditionally in the mid-section with folded cloth, shirtless, and wearing turbans to protect their heads from the burning sun, the barefoot, skeletal looking snake charmers with Peruvian colored skin milled around the mysterious holes looking for signs, inspecting the bottoms of the pits for snakes’ lairs.

Kneeling side by side at the entrance to a black hole in one corner, one man reached his arm in to the shoulder, grasping for something. As the three watched from above, he pulled a long black snake and snakelets out of the dark space, quickly depositing the frightened squirming reptiles into his bag.

Later, the men posed for Hubert’s camera. Before turning them to ash, they proudly held the dead cobras and other poisonous snakes dangling lifeless, rendered harmless, laid out gruesomely next to their baskets and pungis The hunt would end after dark with a huge fire to dispose of the dead animals, which to this day Jasper can still summon the memory.

****

END OF CHAPTER THREE

TO TOGGLE BETWEEN CHAPTERS USE NAVIGATION BUTTONS BELOW

****

Tony Heath is an artist, jazz musician, activist and writer of fiction and essays in Arizona. He and his wife, Kate Scott, co-founded a wildlife advocacy on their ranch in Cochise and Santa Cruz Counties.

Photographs © Tony Heath